Manchester City versus Liverpool is back! The fixture that has defined the Premier League for the best part of a decade is a pivotal game in the title race once again, with Jurgen Klopp’s new-look Liverpool returning to title contention after last season’s failure to finish in the top four.

Pep Guardiola’s City, who achieved a Champions League/Premier League/FA Cup treble last season, host Liverpool at the Etihad on Saturday one point clear of second-place Liverpool at the top of the table.

For three of four seasons between 2018-19 and 2021-22, City and Liverpool finished in the top two positions in the Premier League, each amassing huge points tallies as they drove each other to great success and new benchmarks. But while Guardiola and Klopp remain in charge of their respective teams, the two sides are now markedly different from those that pushed each other so hard in recent seasons.

So what has changed, and how have Guardiola and Klopp rebuilt their sides to reignite the City-Liverpool rivalry? Mark Ogden and Ryan O’Hanlon have analysed and assessed the changes at the Etihad and Anfield to see how the two teams have evolved to become the top two all over again.

Why Man City and Liverpool have been so good

The first time Manchester City and Liverpool competed in a title race, they weren’t that different.

City’s most-used players in 2018-19, by position, were:

Goalkeeper: Éderson

Left-back: Aymeric Laporte

Center-backs: John Stones and Nicolás Otamendi

Right-back: Kyle Walker

Defensive midfield: Fernandinho

Central midfield: David Silva and Bernardo Silva

Left wing: Leroy Sané

Right wing: Raheem Sterling

Center-forward: Sergio Agüero

For Liverpool, meanwhile, it looked like this:

Goalkeeper: Alisson

Left-back: Andy Robertson

Center-backs: Virgil van Dijk and Joël Matip

Right-back: Trent Alexander-Arnold

Defensive midfield: Fabinho

Central midfield: Georginio Wijnaldum and Jordan Henderson

Left wing: Sadio Mané

Right wing: Mohamed Salah

Center-forward: Roberto Firmino

Both teams played the same formations, but had differences in execution. For defensive balance, Guardiola’s full-backs weren’t as aggressive as Liverpool’s, while Liverpool’s midfield wasn’t as attack-oriented.

For Liverpool, Salah and Mane were goal-scoring wingers playing on the side opposite their stronger foot. The full-backs provided the width and the center-forward, Firmino, frequently dropped deeper to create and vacate space for the wingers to break into. With City, Sane and Sterling stayed wide — left-footer on the left, right-footer on the right — and Aguero stayed central, while the two midfielders broke forward to fill the spaces either side of the striker.

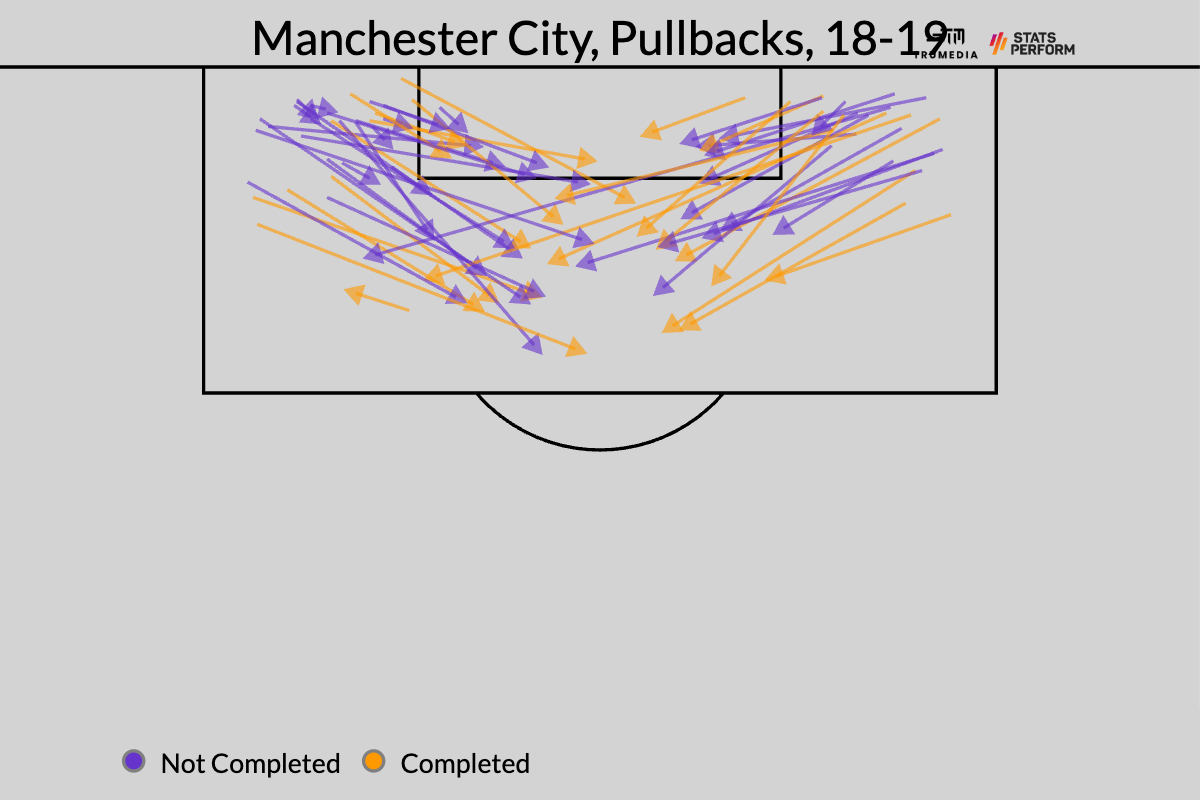

Thanks to the wingers staying wide and the midfielders breaking into the box, City led the league in what’s perhaps the signature attacking move of the Guardiola era: the pullback. That’s when a team gets to the end line and then plays the ball backward into the middle of the box. City created 1.6 pullbacks per match, while only one other team in the league created more than half as many.

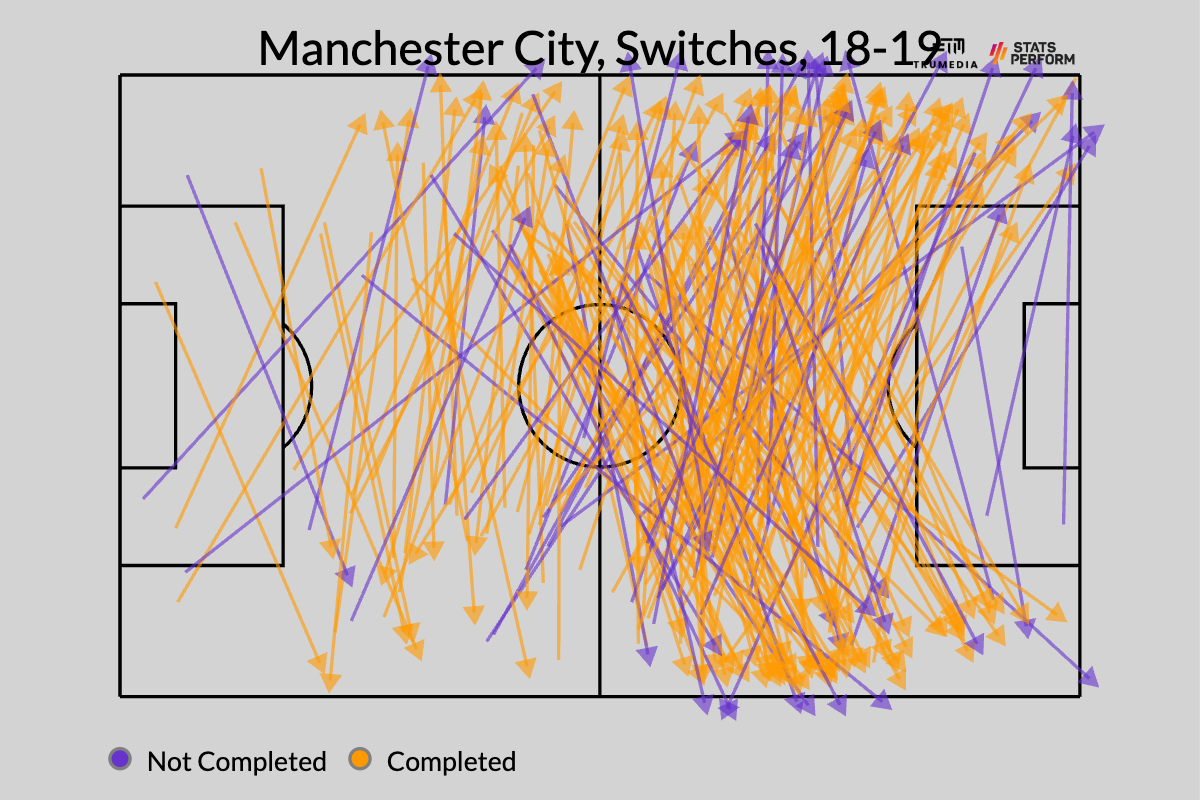

City also led the league in how frequently they attempted to switch play, or quickly play the ball to the opposite side of the field: about six times per 90 minutes. They’d draw the opposition to one side of the field, switch it to the other and then, eventually, the winger would drive to the end line and create a pullback.

These were the classic patterns of Guardiola play — as was their desire for total control. Their field tilt (the share of all the final-third passes in their matches) was a league-best 74%. They also led the league in two of the more basic pressing metrics: passes allowed per defensive action (PPDA) and opposition pass-completion percentage allowed.

Five years later, only four City players remain:

Goalkeeper: Éderson

Left-back: Josko Gvardiol

Center-backs: Rúben Dias and John Stones

Right-back: Kyle Walker

Defensive midfield: Rodri

Central midfield: Bernardo Silva and Julián Álvarez

Left wing: Jérémy Doku

Right wing: Phil Foden

Center-forward: Erling Haaland

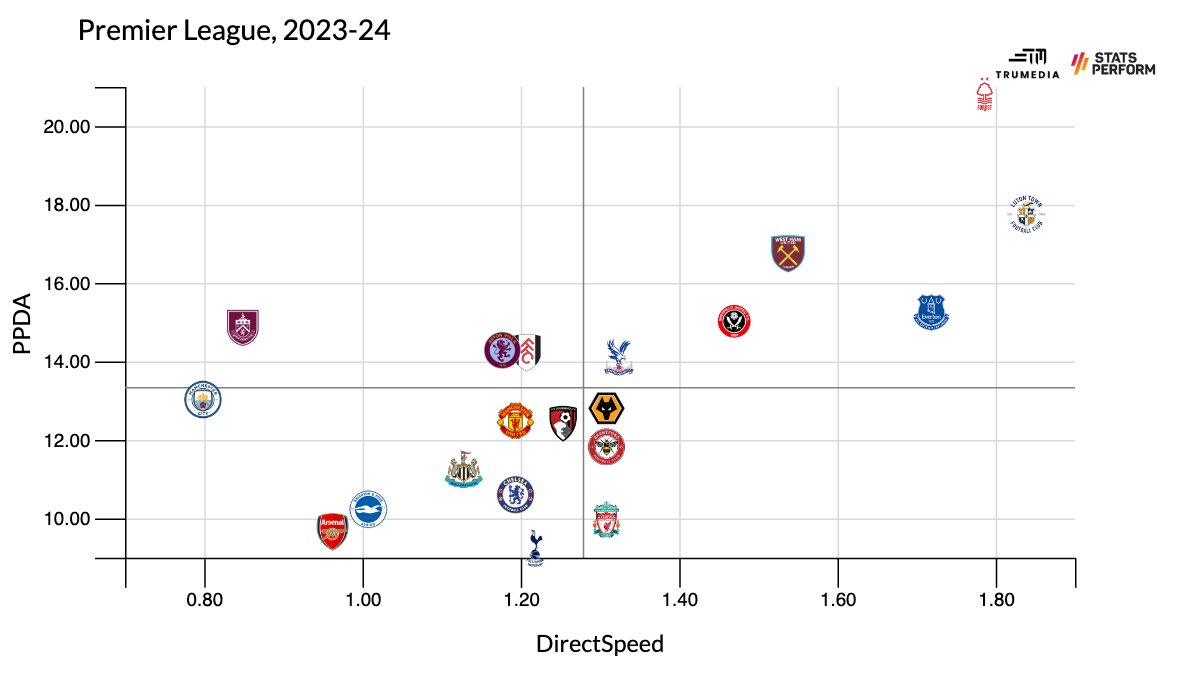

And with those changes in personnel, pretty much all of those stylistic markers have disappeared. City are creating only 0.9 pullbacks per 90 minutes this season — just the 10th most in the 20-team Premier League. They’re playing 2.7 switches per 90, which is the 12th most in the league. Their pressing rates have plummeted, too: down to 11th in PPDA and 11th in opponent pass-completion percentage.

Despite all of that, they still lead the league in field tilt — how might you do that if you’re not preventing your opponent from getting into your defensive third? You move very slowly once you get the ball into their defensive third.

In the past, City’s best defense was, well, not having to defend. But now, with Gvardiol and a five-years-older Walker essentially functioning as third and fourth center-backs — these are not traditional full-backs — City are happy to let opponents attack them. And once they get the ball, City are not switching play and attacking weak spots to create pullbacks. They’re methodically and deliberately moving the ball until Haaland can find enough space to smash one in.

Typically, teams that press don’t move the ball upfield quickly because it’s already up the field. And teams that don’t press do move the ball quickly because one of the advantages of not pressing is that it encourages your opponent to push bodies forward and then creates all kinds of space behind their defensive line for you to attack into. City have broken that relational chain — and so have Liverpool, just in the opposite direction:

(Direct speed measures how quickly a team moves the ball upfield in meters per second.)

(Direct speed measures how quickly a team moves the ball upfield in meters per second.)

Back in 2018-19, Liverpool didn’t stand out in too many statistical ways when compared to City. They were second or third best in just about every attacking and defensive metric. They pressed high, kept the ball in the attacking third, lived in the opposition penalty area — all that good stuff that produces great teams. They just weren’t as great as perhaps the greatest English team of all time. And for as excellent as Liverpool were, they weren’t weird: two attacking full-backs, three great attackers, and a conservative midfield that covered everything up.

However, the one area where Liverpool really differed from their peers was in the number of possessions they had per game. Klopp’s team averaged 99 possessions per game — more than everyone other than Everton and two of that season’s relegated sides, Huddersfield Town and Fulham. City, meanwhile, were last with 86 possessions per game. While both clubs played most of their matches in the opposition half, City accomplished it without the ball turning over as much, while Liverpool did it with possession constantly changing hands.

This year, possession is still changing hands quite often for the Reds — down to 91 possessions per game, though still fourth in the league amidst a Premier League-wide slowdown in play. But let’s take a quick look and their new most-used collection of players.

+ There are no comments

Add yours